|

| Big Hair and Plastic Grass, by Dan Epstein, 2010. That's Oscar Gamble with the amazing Afro. |

|

| Stars and Strikes, by Dan Epstein, 2014. Featuring Ralph Garr in shorts, and Mike Schmidt without a mustache. |

|

| The Russians, by Hedrick Smith, 1976. |

|

| Little Green Men, by Christopher Buckley, 1999. |

|

| How to Fight Presidents, by Daniel O'Brien, 2014. |

|

| Kirk Douglas promoting The Ragman's Son, 1988. |

|

| Ike's Bluff, by Evan Thomas, 2012. |

|

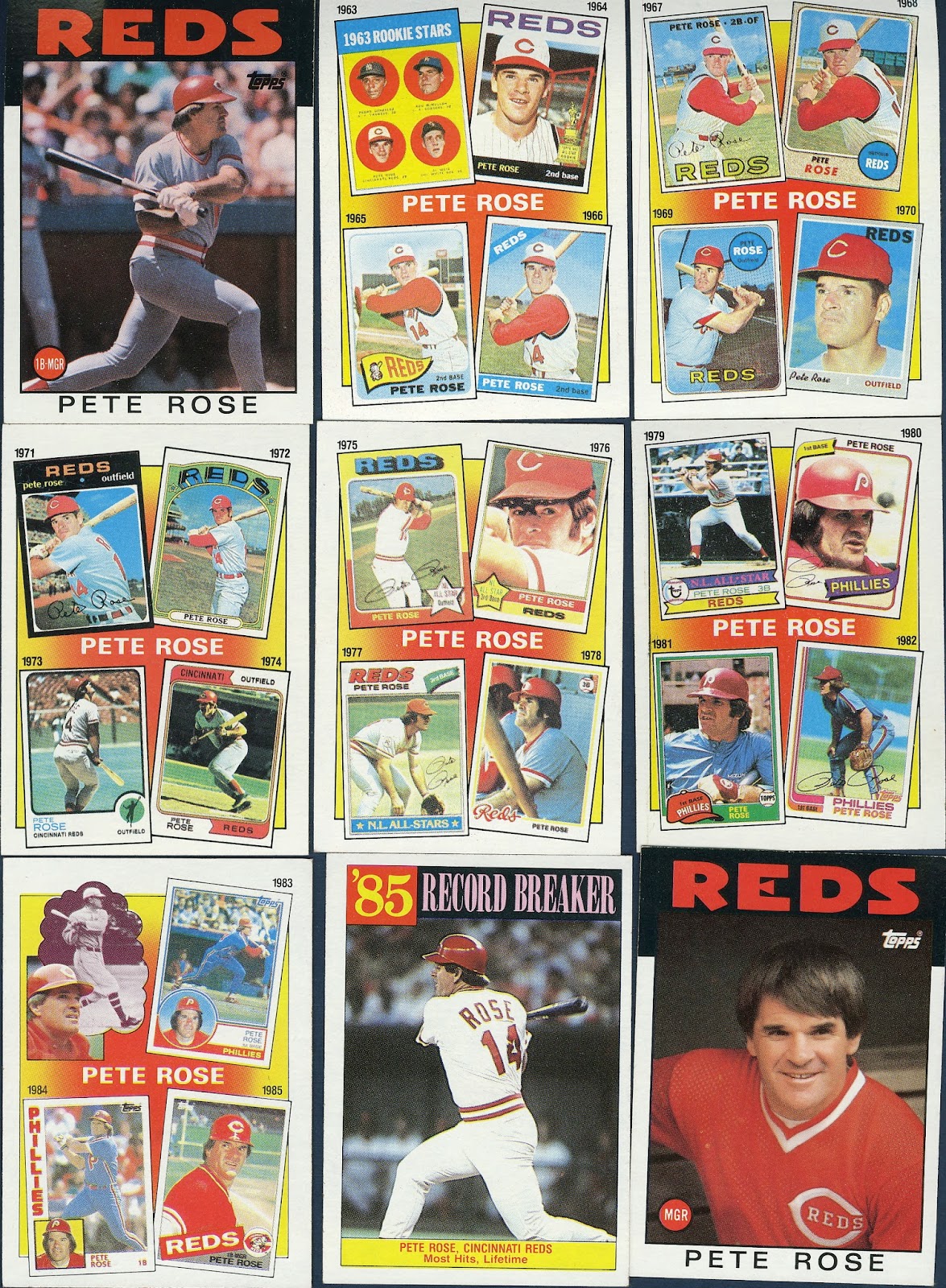

| Hustle, by Michael Sokolove, originally published in 1990, updated in 2005. |

I had a very productive reading year, and I managed to read

27 books in 2014. Since it’s almost the end of 2014, and the end of the year is

the prime time for best-of lists, here’s my list of the best books I read this

year. (The links will take you to the full review of the book.)

Big Hair and Plastic Grass and Stars and Strikes, by

Dan Epstein. Epstein is a great writer who has a big heart for both baseball

and the 1970’s. I read both of his books about 1970’s baseball this year, and I

thoroughly enjoyed them. Big Hair and

Plastic Grass is a season-by-season account of the 1970’s, and Epstein

makes the larger-than-life personalities of the time come to life. Epstein

writes that the decade of the 1970’s saw more changes in baseball than all the

other decades before, and I have to agree with him. Stars and Strikes is an in-depth look at the 1976 season, and it’s

a great portrait of a game on the edge of some huge changes, like free agency.

Epstein’s enthusiasm for baseball and 1970’s pop culture comes through in both

books, and I like that he clearly enjoys what he’s writing about. Reading

Epstein’s books will make you want to buy a Pontiac Firebird with a t-roof,

throw on some Eagles 8-tracks, and grow a mustache. You should follow his

Facebook pages, in which he wittily wishes 1970’s baseball players a funky

birthday.

The Russians, by

Hedrick Smith. I read The Russians during

this year’s Sochi Olympics, and the book helped me understand the

contradictions of Russia much better. Even though Smith’s book was published in

1976, his insights into the Russian culture and character are still very

relevant. Smith was the Moscow bureau chief for The New York Times from 1971-74, and in 1974 he won the Pulitzer

Prize for International Reporting for his articles about life in the Soviet

Union. I was lucky enough to intern for Hedrick Smith during college in the

fall of 2001, as he was finishing up the excellent documentary “Rediscovering

Dave Brubeck.” In The Russians, Smith

deftly exposes one of the many contradictions in Soviet society: that the

supposedly classless society was actually just as stratified between the haves

and have-nots as the West was, if not more so.

Little Green Men, by

Christopher Buckley. Little Green Men is

a tremendously funny satire. Christopher Buckley can make me laugh like few

other authors can. When I read this book I really needed some laughs, and Little Green Men more than delivered. I

wish there were a movie version with Stephen Colbert playing the book’s hero,

the blowhard political commentator John Oliver Banion, who gets abducted by

aliens and heads up the “Millennium Man March” on Washington.

How to Fight Presidents, by Daniel O’Brien. O’Brien mixes humor with historical fact in

this book, which is a guide on how to fight former U.S. Presidents. The book

assumes that you have to go back in time and engage them in hand to hand

combat. This would be a daunting task, since most of our Presidents have been

pretty badass. The chapter headings are hilarious. Two of my favorites are:

“Thomas Jefferson just invented six different devices that can kill you,” and

“Franklin Pierce is the Franklin Pierce of fighting, which is to say, he is a

bad fighter.” If you’re a history buff, this book will make you laugh, and you’ll

also learn something along the way. Like the one time when James Monroe threatened

his secretary of the treasury with a set of fireplace tongs.

The Ragman’s Son,

by Kirk Douglas. An excellent Hollywood autobiography, Douglas pulls no punches as

he tells the story of how he rose from abject poverty to become one of the

biggest movie stars of the 1950’s and beyond. The Ragman’s Son is written with honesty, and Douglas isn’t afraid

to show the reader his faults, which makes it a great autobiography. Douglas is

a complex man, and The Ragman’s Son

is a fascinating look at the life and mind of one of the greatest film actors

of the last 60 years. Douglas just turned 98 in December, and old movie fans

like me can be glad that he’s still with us.

Ike’s Bluff, by

Evan Thomas. Evan Thomas’s 2012 book Ike’s

Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World, completely refutes

the stereotype of Dwight Eisenhower as a caretaker president who only cared

about his golf handicap. Thomas focuses his book exclusively on Eisenhower’s

foreign policy, and he paints a portrait of an engaged leader who was extremely

skilled at using psychology to get what he wanted. Thomas is incisive about

Eisenhower’s complex personality, using excerpts from the medical diary of

Howard Snyder, Eisenhower’s doctor, to shed light on Ike’s mood swings. Despite

his seemingly endless patience at the bridge table, Ike had a terrible temper which

he struggled to keep under control, and he once hurled a golf club at Dr.

Snyder. I learned a lot about Eisenhower from Ike’s Bluff, and he comes off as a canny man who did his best to

keep the Cold War from turning hot. The book is an excellent study of presidential

leadership.

Hustle: The Myth, Life, and Lies of Pete Rose, by Michael Sokolove. Sokolove examines many

different parts of Pete Rose’s life and career in this excellent book. One

chapter deals with Rose’s close friendships with many sportswriters, which

probably kept the media off of his back until his gambling scandal exploded in

1989. Sokolove understands the contradiction of Pete Rose, and other athletes:

that a man can be a great baseball player and at the same time be a terrible

human being. Hustle is essential

reading for any baseball fan.