|

| Original dust jacket cover of The Right Stuff, by Tom Wolfe, 1979. |

|

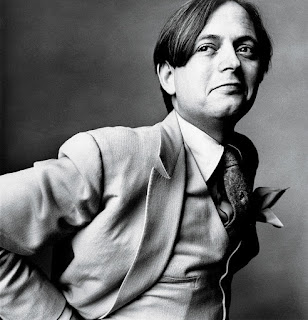

| Tom Wolfe, photographed by Annie Leibovitz in 1980. His look seems to be saying, "Yes, I am the Tom Wolfe!" |

|

| The Mercury 7 astronauts, 1960. |

Tom Wolfe, writing in his classic book The Right Stuff about the Mercury 7 astronauts, the first American

men in space, gets directly to the heart of what made these men tick. Most of

the Mercury 7 astronauts were military test pilots, and being a military test

pilot is about the hardest damned thing there is. It is the apex of singular

macho pride. Those pilots are pushing the envelope of those planes every single

day! And they are doing it by themselves! Sure, there's a whole crowd of

support people on the ground, but up there, in the wild blue yonder, you are it! There's just you, and your

judgement, your daring, your reflexes, your instincts, your STUFF, responsible

for that plane. And if you have the right stuff, you'll bring that plane back

safely. If you don’t have the right stuff, well, there’s a 23% chance you’ll

die in an accident.

What exactly is “the right stuff”? Wolfe never gives the reader

a brief definition, but it’s a combination of several things, all adding up to

a cool unflappability in the face of possible death.

Wolfe writes of “the right stuff,” “Perhaps because it could

not be talked about, the subject began to take on superstitious and even

mystical outlines. A man either had it or he didn’t! There was no such thing as

having most of it. Moreover, it could

blow at any seam.” (p.21)

There were numerous pitfalls along the way for anyone who

wanted to make a career out of being a military pilot. Early in the book, Wolfe

describes how the status of pilots was assessed in terms of the right stuff:

“Nor was there a test to

show whether or not a pilot had this righteous quality. There was, instead, a

seemingly infinite series of tests. A career in flying was like climbing one of

those ancient Babylonian pyramids made up of a dizzy progression of steps and

ledges, a ziggurat, a pyramid extraordinarily high and steep; and the idea was

to prove at every foot of the way up that pyramid that you were one of the

elected and anointed ones who had the

right stuff and could move higher and higher and even-ultimately, God

willing, one day-that you might be able to join that special few at the very

top, that elite who had the capacity to bring tears to men’s eyes, the very

Brotherhood of the Right Stuff itself.” (P.17-8)

Wolfe returns to the image of the ziggurat numerous times

throughout the book, and it’s a perfect metaphor that lingers with the reader.

The Right Stuff introduces

us to the world of American test pilots after World War II, and to one of the

most colorful characters in the book, Chuck Yeager, perhaps the ne plus ultra of the right stuff. Yeager

was cool and laconic, and never seemed to feel the pressure of his job, even during

his successful attempt to break the sound barrier in 1947 in the Bell X-1.

Wolfe vividly describes the California desert around Muroc

Field, now known as Edwards Air Force Base, where much of the testing of the

1940’s and 1950’s happened. Wolfe writes of the landscape: “Other than

sagebrush the only vegetation was Joshua trees, twisted freaks of the plant

world that looked like a cross between cactus and Japanese bonsai. They had a

dark petrified green color and horribly crippled branches. At dusk the Joshua

trees stood out in silhouette on the fossil wasteland like some arthritic

nightmare.” (p.36)

Yeager basically disappears from the book once the Mercury 7

astronauts were chosen, and The Right

Stuff focuses on the sometimes complicated relationship the seven men had

with each other. One of my favorite parts in the whole book was Wolfe’s

description of astronauts Gus Grissom and Deke Slayton:

“As soon as Gus arrived at the Cape, he would put on clothes

that were Low Rent even by Cocoa Beach standards. Gus and Deke both wore these

outfits. You could see them tooling around the Strip in Cocoa Beach in their

Ban-Lon shirts and baggy pants. The atmosphere was casual at Cocoa Beach, but

Gus and Deke knew how to squeeze casual until it screamed for mercy. They

reminded you, in a way, of those fellows whom everyone growing up in America

had seen at one time or another, those fellows from the neighborhood who wear

sport shirts designed in weird blooms and streaks of tubercular blue and

runny-egg yellow hanging out over pants the color of a fifteen-cent cigar, with

balloon seats and pleats and narrow cuffs that stop three or four inches above

the ground, the better to reveal their olive-green GI socks and black bulb-toed

bluchers, as they head off to the Republic Auto Parts store for a set of

shock-absorber pads so they can prop up the 1953 Hudson Hornet on some

cinderblocks and spend Saturday and Sunday underneath it beefing up the

suspension.” (P.132-3)

I love that description. It’s so wonderfully vivid. You can

see Gus and Deke very clearly in your mind. It’s passages like this that make

Tom Wolfe such a great writer. It’s a passage that you would never read in a

more “scholarly” book about the Mercury space program, but because it’s a more

unorthodox way of writing, and more similar to a description that you would

read in a novel, Wolfe gets you closer to the truth of what Gus and Deke were

probably like.

The long sections of the book where Wolfe re-creates the

astronaut's flights are amazing. It gets as close as we can to being inside

their heads during those moments. And it seems to prove that picking astronauts

from test pilots was the right thing to do, despite the quibbles of some climbing

the ziggurat who squawked that the astronauts weren’t even really pilots

because they weren’t in full control of the capsule! They were just passengers,

there to enjoy the view! Sure some of the Mercury flights were relatively easy,

but some were not-Gordon Cooper's flight especially. You needed someone who

knew how to handle that pressure and make the right decisions in real time.

Someone who had, yes, the right stuff!

John Glenn is one of the most vivid figures in the book, as

he quickly became the chief media spokesperson for the Mercury 7 astronauts.

Glenn was always amiable, and while some of the other astronauts looked askance

at his goody two-shoes attitude, Tom Wolfe rather enjoyed Glenn. Wolfe said of

Glenn in a 1981 interview: “It’s very rare to see a man in our day-outside the

Church-who is a moral zealot and who doesn’t hide the fact; who constantly

announces what he believes in and the moral standards he expects people to

follow. To me that’s much rarer and more colorful than the Joe Namath-rake figure

who is much more standard these days.” (Conversations

with Tom Wolfe, p.164)

After Glenn’s successful flight in 1962, in which he became

the first American to orbit the earth, President John F. Kennedy’s father, old

Joe Kennedy himself, broke down in tears when he met Glenn. Wolfe wrote, “That

was what the sight of John Glenn did to Americans at that time. It primed them

for the tears. And those tears ran like a river all over America. It was an

extraordinary thing, being the sort of mortal who brought tears to other men’s

eyes.” (p.282)

From a historical perspective, more than thirty five years

after The Right Stuff was published,

Wolfe was right to focus a lot of attention on Glenn, as he became the biggest

hero from the early space program. Thanks to Glenn’s four terms in the United

States Senate, along with his return to space in 1998, his celebrity among the

average American far outstrips that of Alan Shepard, who beat out Glenn for the

honor of commanding the first Mercury flight in 1961.

The Right Stuff was

an instant hit among both critics and the public. In the same 1981 interview

quoted above, Wolfe was asked about the feedback he got from the astronauts

about the book. Wolfe replied, “I’ve had varied reactions. Some of them really

seemed to like it, or at least to have said that it’s accurate, which means

more to me than whether or not they really liked it. Alan Shepard, I know,

doesn’t like it because every time he’s asked he says, ‘I haven’t read it and

I’m not going to.’” (Conversations with

Tom Wolfe, p.164)

Wolfe admitted that The

Right Stuff was a difficult book to write, and it had a long gestation

period. Wolfe had first gotten intrigued by the astronauts at the very end of

the Apollo program, as he wrote about Apollo 17, the last mission to the moon

in December of 1972, for Rolling Stone magazine.

Wolfe quickly knew the material could be expanded to a book, as he said in a

1973 interview with Publishers Weekly, “the

title will probably be The Right Stuff,”

and “The reigning fantasy is that it will be ready by fall.” (Conversations with Tom Wolfe, p.31) That

obviously didn’t happen, as Wolfe admitted in 1979, “I would do almost anything

at times to avoid working on it…which may be the reason I published three other

books during that period.” (Conversations

with Tom Wolfe, p.107)

One of those other books was the essay collection

Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter &

Vine, published in 1976,

which I reviewed here. A highlight of

Mauve Gloves was the article “The Truest

Sport: Jousting with Sam and Charlie,” about fighter pilots in Vietnam. Wolfe

comes close to naming “the right stuff” in this passage: “Within the fraternity

of men who did this sort of thing day in and day out-within the flying

fraternity, that is-mankind appeared to be sheerly divided into those who have

it and those who don’t-although just what

it

was…was never explained.” (

Mauve

Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine, p.45)

Wolfe humorously discussed his problems finishing The Right Stuff in a 1981 interview with

Joshua Gilder, published in Saturday Review: “I even got to the point where I wore

clothes in which I couldn’t go out into the street. Such as khaki pants; you

know, I think it’s demeaning. I can’t go out into the street in khaki pants or

jeans.” Gilder then asks the natural follow up question: “You own a pair of

jeans?” Wolfe answers, “I have one pair of ‘Double X’ Levis, which I bought in

La Porte, Texas, in a place that I was told was an authentic Texas cowboy

store, just before I started working on The

Right Stuff. I’ve had them on, but I’ve never worn them below the third

floor. So I put on a pair of khaki pants and a turtleneck sweater, a heavy

sweater.” (Conversations with Tom Wolfe, p.161)

In another 1981 interview, which was not published until

1983, Wolfe discussed the structural challenges of The Right Stuff. “The book was extremely difficult to write. There

was no central character, no protagonist…The problem of giving the book a

narrative structure, some sort of drive and suspense, was quite tough.” (Conversations with Tom Wolfe, p.182) Wolfe

is right about the book not having a central character. If Chuck Yeager had

been chosen to be an astronaut, it would have been easy-he clearly would have

been the central figure. As it is, Yeager looms large in the beginning of the

book, and then disappears once the astronauts for the Mercury program are selected,

at which point John Glenn becomes the central figure in the narrative.

In that same interview, Wolfe was asked if he was pleased

with the reception of the book. He said, “I felt that it was my best book. I

very consciously tried to make the style fit the particular world I was writing

about, mainly the world of military pilots. To have had a prose as wound up as

the prose of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid

Test would have been a stylistic mistake.” (Conversations with Tom Wolfe, p.181)

Tom Wolfe devotees shouldn’t worry about the prose style

being too laid back, there are still plenty of exclamation points, and some pet

Wolfe phrases reappear throughout the book, as people are “packed in shank to

flank,” (p.85) and the reader is told to “deny it, if you wish!” (p.303) However,

no one in The Right Stuff is described

as arteriosclerotic, which was a pet word of Wolfe’s in his first book, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline

Baby.

The Right Stuff feels

like a perfect book for its time. Wolfe’s portrait of the Mercury 7 astronauts as

genuine American heroes resonated just as America ended the bewildering decade

of the 1970’s, in which she had seen her power and might slip, and moved into

the more patriotic 1980’s, led by Ronald Reagan, who loved stories about

American heroism. I wonder if Ronnie ever read The Right Stuff? Well, he probably saw the movie.

Tom Wolfe is at his very best throughout The Right Stuff, and it’s one of the

best books of his long career.