|

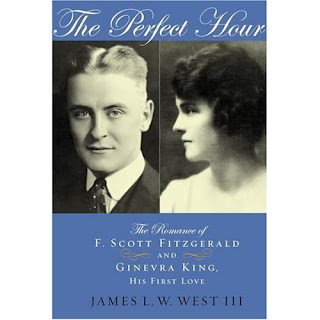

| Cover of The Perfect Hour, by James L.W. West III, 2005. |

|

| Professor James L.W. West III, one of the leading scholars on the life and work of F. Scott Fitzgerald. |

In the studies of F. Scott Fitzgerald, one of the more important people in Fitzgerald’s life was Ginevra King. Fitzgerald and King met fewer than a dozen times in person, so how could she possibly be so important to him? Ginevra King was Scott’s first serious girlfriend, and she inspired many of his female characters in his fiction. In the 2005 book The Perfect Hour: The Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ginevra King, His First Love, by esteemed Fitzgerald scholar James L.W. West III, the full story of Scott and Ginevra’s romance is finally told.

Scott and Ginevra met in Saint Paul in January of 1915, at the home of Marie Hersey, a mutual friend. Fitzgerald was a sophomore at Princeton University when he met Ginevra, who was two years younger and a student as Westover, a girl’s boarding school in Connecticut. Fitzgerald was from Saint Paul, and the King family was from Chicago. The Fitzgeralds still enjoyed high social standing in Saint Paul, but the family was coasting as the money slowly ran out. In contrast, the Kings were very wealthy, and Ginevra’s father was a stockbroker. The Kings had a large summer residence in Lake Forest and were building a four-story mansion in the Gold Coast area of Chicago.

Scott and Ginevra were instantly smitten with each other and carried on a long-distance romance for two years that was largely conducted through letters. Unfortunately, after their break-up, Scott badgered Ginevra to destroy all of his letters to her. (The modern-day equivalent would be deleting one’s texts, I suppose.) Ginevra’s original letters do not survive, so Scott presumably destroyed those, but before doing so, he hired someone to type them up, and had them bound in a book, which is 227 pages long! (Fitzgerald did not type himself, ergo he must have found someone to type the letters for him.) After Fitzgerald’s death, his daughter Scottie gave the letters back to Ginevra. Ginevra’s descendants allowed West to have full access to her letters, which they have now donated to the Princeton University Library, where they reside with Fitzgerald’s papers.

Thanks to his access to Ginevra’s letters, West can show us that Ginevra reciprocated Scott’s affections, at least for a while. Scott and Ginevra met in person just eight times that we know of. Six of those meetings occurred in 1915, and just two in 1916, indicating that the flame had cooled considerably by then. They broke up in January 1917, two years after their initial meeting. Ginevra later told Scott’s first biographer that she didn’t even remember if she had ever kissed Scott. Ouch. By the summer of 1918, Ginevra was engaged to Billy Mitchell, a family friend who was a naval aviator—the most romantic type of soldiering a young man could do in World War I. Unsurprisingly, Ginevra went for the super-wealthy WASP friend of the family rather than the aspiring novelist with no trust fund from the Irish Catholic family.

Scott was invited to Ginevra’s wedding, which took place in Chicago in September of 1918, but in all likelihood, he did not attend, as he was stationed at Camp Sheridan in Alabama. Fitzgerald did paste the wedding invitation into his scrapbook, along with a newspaper article describing the wedding. By the time of Ginevra’s wedding, Scott had already met his future wife: the vivacious southern belle Zelda Sayre.

Fitzgerald’s personal life always informed his fiction, and there are numerous connections between the two. He used Ginevra as the model for several characters. In his first novel, This Side of Paradise, elements of Ginevra appear in both Isabelle Borge and Rosalind Connage, two flames of the narrator (and Fitzgerald proxy) Amory Blaine. Ginevra was also the inspiration for Judy Jones, the femme fatale in one of his finest short stories, “Winter Dreams,” first published in 1922.

And what about The Great Gatsby, old sport? Ginevra most likely inspired aspects of the character of Daisy Fay Buchanan. It’s an oversimplification to say that Ginevra was Daisy. As West writes, “Daisy Buchanan is a composite.” (p.96) Aspects of both Ginevra and Zelda went into Daisy’s character, but Daisy’s wealth and social status are much more in line with Ginevra King’s rather than Zelda Sayre’s.

The narrative part of The Perfect Hour is rather short, just over 100 pages. Fortunately, West has also included some of Ginevra’s diary entries, five of her letters to Fitzgerald, and the texts of “Babes in the Woods” and “Winter Dreams” two of the short stories that Ginevra helped to inspire. For a Fitzgerald fan, The Perfect Hour is a must-read, as West tells Scott and Ginevra’s story honestly, without hyperbole or exaggeration.

No comments:

Post a Comment